Things are going from bad to worse in Japan: 7 years after BOJ chief Kuroda launched QQE (subsequently with yield curve control) while monetizing tens of billions in ETFs, the central banks has failed to boost either Japan's economy or its inflation, both a dismal byproduct of Japan's record debt load. So now that the BOJ has failed to remedy what was the consequence of massive debt loads, Japan has a cunning plan: unleash another tsunami of debt.

According to the Japan Times, Japan is set to "re-embrace the power of public spending" - because apparently the country with the world record setting 250% debt/GDP somehow did not embrace public spending before - with one of its biggest ever stimulus packages. Pointing to slowing global growth, a higher sales tax and a string of natural disasters, policymakers in Tokyo are the latest to join the worldwide shift toward a double-barreled approach of supporting the economy through fiscal measures and ultraloose monetary policy, which as we have noted before is a preamble to MMT and full-blown debt monetization by the government.

That's good news for the Bank of Japan, which has "appeared" (but only appeared, because it now owns so many of Japan's ETFs it has to start lending them out to prevent a market freeze) reluctant to ramp up its own massive stimulus program, as it strains at the limits of effectiveness.

As a result, in less than a month, expectations in Japan for a "modest" stimulus package with a face value of ¥5 trillion ($46 billion) have quadrupled to ¥20 trillion, despite having the developed world's largest public debt load. And there is much more to come. Putting this in context, even a "modest" ¥10 trillion in fresh fiscal stimulus would still make it Japan's biggest package since extra budgets were drafted to deal with the widespread destruction from the 2011 mega-quake and tsunami, and the emergency spending that followed the 2008 global financial crisis.

The biggest irony of all - the recent sales tax hike, which was meant to put Japan's debt on a more credible footing - is just that scapegoat the Abe administration needs to launch a fresh stimulus ensuring a surge in Japan's debt. Then there is the recent typhoon and a weakening world economy, both of which were cited by Abe as rising risks for a recession that would tarnish the legacy of his "three arrows" Abenomics project to restore stable growth.

For Japan it may be too late even with additional stimulus: the country's economy is expected to shrink 2.7% this quarter as exports continue to slump and consumption is whiplashed by the tax increase to 10%. Data out earlier this week already showed sharper-than-expected drops in retail sales and factory output, suggesting the economic contraction may be stronger than expected and will add to calls for a substantial package.

Of course, by now nobody believes that massive debt injections can help Japan - if that was the case, its 250% debt/GDP would have long ago made Japan the world's best performing economy. Instead, the new funding merely reflect a need to shore up Abe's political support after recent scandals, with a possible view to seek another term as prime minister or call an early election — a favorite tactic of Japan's longest-running prime minister.

"We don't really need this huge level of stimulus now," Shinichiro Kobayashi, an economist at Mitsubishi UFJ told the Japan Times. "Somewhere around ¥5 trillion should be more than enough. This is not about the economy but motivated mainly by political reasons with popularity and a possible election in mind."

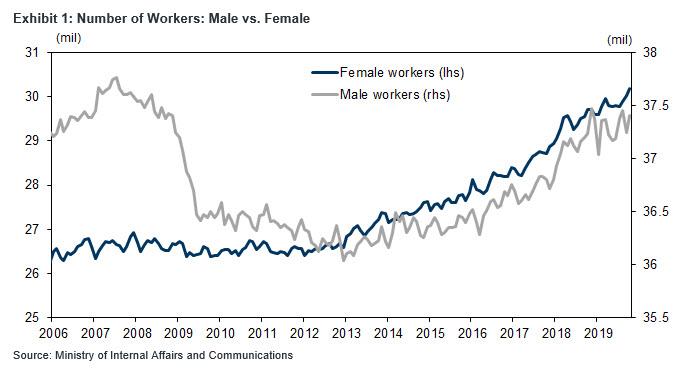

Meanwhile, some economists - but certainly not the majority - wonder if extra spending equivalent to 1.8% of Japan's GDP would actually be cost-effective. Given a labor shortage in the construction sector, extra public works spending would simply reduce the availability of scarce workers for the private sector, crimping output there. Meanwhile, the latest Japanese employment data reports of a perplexing picture: Japan's labor force is soaring as increasingly more elderly women enter the workforce. As Japan reported last night, the number of female workers rose by 150,000, marking the third straight monthly uptick, driven by increases for females aged 55-64 (+140,000) and 65 and over (+30,000). The total number of female workers reached another record-high of 30.18 million.

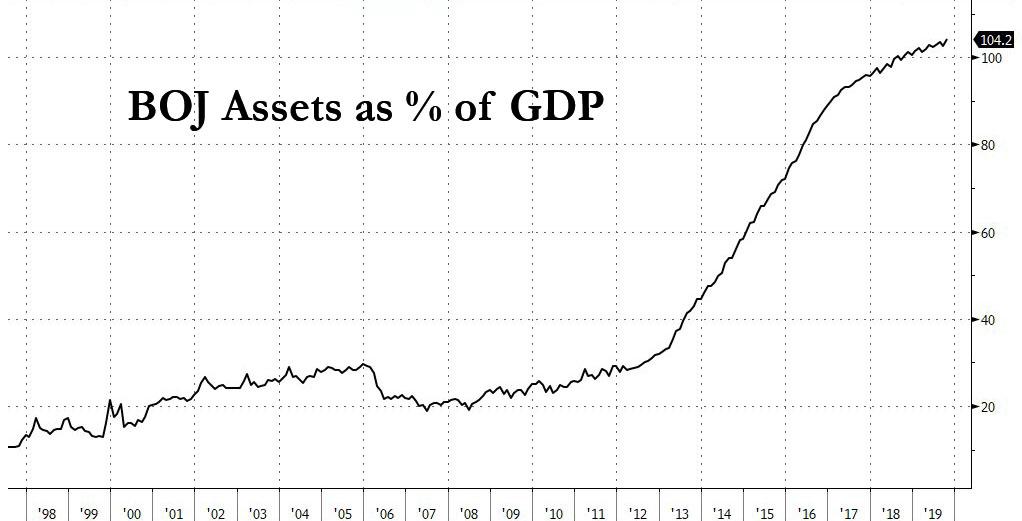

Of course, no spending bill could be possible with a central bank to monetize it, and on Thursday, BOJ Gov. Haruhiko Kuroda called on the government to spend wisely with its spending package, even though there is now little doubt now that a hefty package is now in the works. As for the BOJ, we are long past the point where anything matters: in addition to holding nearly 90% of all Japanese ETFs, the central bank owned 104% of the country's GDP in bonds.

"Japan is the easiest place in the developed world to increase spending," said Masamichi Adachi, chief Japan economist at UBS Securities Co. "Politicians love it and they've probably gotten tired of all the warnings of a debt crisis that hasn't actually happened over the last decade."

Yet even though both the IMF and ECB are now urging everyone to rush into the warm, terminal embrace of MMT - i.e., helicopter money, i.e., direct debt monetization - not everyone has lost their minds. Former deputy Prime Minister Katsuya Okada, now a member of the opposition, says that the loosening fiscal stance of politicians among both the ruling and opposition camps is alarming.

"I'm very concerned about this emerging mood that there's no need to address our spending and revenue," Okada said. "There's no doubt that Modern Monetary Theory has given some politicians the feeling of a sort of endorsement for more spending. But a frog in lukewarm water will end up boiled if the temperature keeps rising."

And speaking of warnings about boiling frogs, nobody is better suited to give on than former BOJ governor, Toshihiko Fukui, who presided over the Bank of Japan from 2003 to 2008, and who according to newly released documents resisted engaging in more QE at the time, and also regretted raising interest rates faster.

Fukui - who left office in March 2008 when the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis was rippling through the American economy - felt a need "to avoid the risk that the threshold to fiscal policy became too low" if the Bank of Japan held too much long-term government debt, he told BOJ researchers during interviews held in 2016 to 2017. Of course, with the BOJ now holding over 100% of total debt, no politician can credibly make the case for fiscal caution, especially since the BOJ can just keep on monetizing the debt until eventually the yen disintegrates.

But perhaps more importantly, Fukui sounded an urgent note of doubt on ultralow policy interest rates, saying 1% is the lowest level at which rates can function. While he is probably right - with Bank of America recently finding that in a world of ZIRP and NIRP, currency moves are no longer impacted by rates - bankers now find themselves in a world of negative borrowing rates.

Records of the interviews, published recently following a disclosure request under Japan's freedom-of-information law, show how Fukui wrestled with a problem that has ballooned since his tenure.

As the Nikkei reports, under current current BOJ head Kuroda, the bank's purchases of government bonds peaked at 80 trillion yen ($730 billion) a year. They have since fallen to around 20 trillion yen a year but remain far higher than the level that prompted Fukui's misgivings.

Yet it may come as a surprise to some, but the BOJ began quantitative easing under Fukui's immediate predecessor, Masaru Hayami. By the time Fukui took over, the pace of bond buying had jumped to 1.2 trillion yen a month.

"After taking office, I quietly decided to myself that I would not increase buying of long-term debt," Fukui said in the interviews. "I also felt conflicted about quantitative easing. ... I understood that that killing the function of interest rates would weaken the mechanism for economic regeneration," he said, explaining precisely how in their pursuit of all market time highs, central banks killed the underlying economies.

If only more economists knew now what Fukui knew then, the world economy would be so much stronger...

There is another notable parallel between now and then: the Fukui-era BOJ policy also offers possible parallels for an eventual exit strategy from the central bank's current phase of quantitative easing. As it is now well-known, central banks tried and failed miserably to normalize monetary policy in the 2016-2018 period. Under Fukui, the BOJ also ended quantitative easing and its zero-interest policy in 2006. But he described its subsequent interest rate hikes, which took its benchmark short-term rate to just 0.5%, as "incomplete."

"If we had reached about 1%, I would have felt a little at ease when handing over the reins," Fukui said, according to the records. Another reason for this is that it would have given the bank more latitude to cut interest rates later, he explained.

There is of course a simple reason why Japan couldn't raise rates more than 0.5% - Japan has too much debt. And now it has much, much more debt, making any attempts at monetary tightening impossible.

Of course, critics say the timidity of past easing measures is one reason Kuroda's BOJ was forced to resort to drastic action, such as greatly stepped-up bond buying and purchases of exchange-traded funds. That's wrong: Kuroda merely did what every central banker now does - blow an ever bigger bubble in hopes of reversing the devastation unleashed when the prior bubble burst. As for what happens in the future, how deep the depression will be once the current bubble bursts, and how such a bubble-bust cycle could ever have a happy ending ... well, that is someone else's problem.

Commenti

Posta un commento