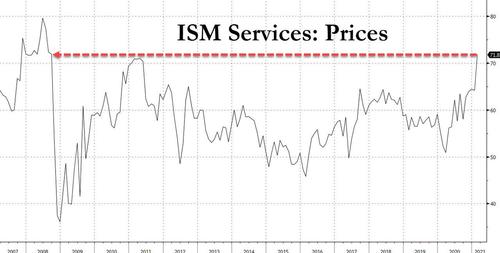

... the reality is that these indexes don't do justice to the price panic on the ground. For that we check in on what some of the respondents were saying in the latest Mfg ISM, which were in a word - shocking:

- "Things are now out of control. Everything is a mess, and we are seeing wide-scale shortages." (Electrical Equipment, Appliances & Components)

- "Prices are rising so rapidly that many are wondering if [the situation] is sustainable. Shortages have the industry concerned for supply going forward, at least deep into the second quarter." (Wood Products)

- "Prices are going up, and lead times are growing longer by the day. While business and backlog remain strong, the supply chain is going to be stretched very [thin] to keep up." (Machinery)

- "Supply chains are depleted; inventories up and down the supply chain are empty. Lead times increasing, prices increasing, [and] demand increasing. Deep freeze in the Gulf Coast expected to extend duration of shortages." (Chemical Products)

- "We have seen our new-order log increase by 40 percent over the last two months. We are overloaded with orders and do not have the personnel to get product out the door on schedule." (Primary Metals)

Yet while executives at virtually all businesses are now openly panicking about soaring input prices, the Fed is not perhaps because the central planners hope that the burst in prices will be temporary (a function of trillions in stimulus) as wages once again fail to rebound along with costs.

But is the Fed's complacent optimism justified? For the answer we go to a report published overnight by Goldman economists which sees to "size inflation rises in a reopening boom" that is now set to take place in the next few months as covid is finally defeated.

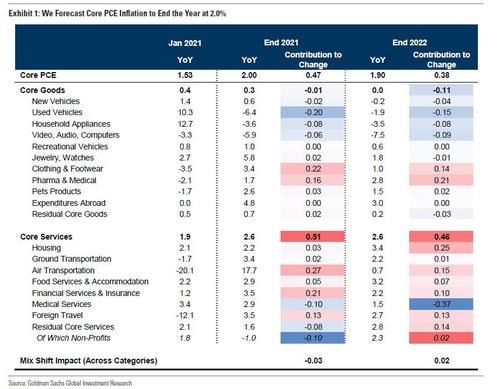

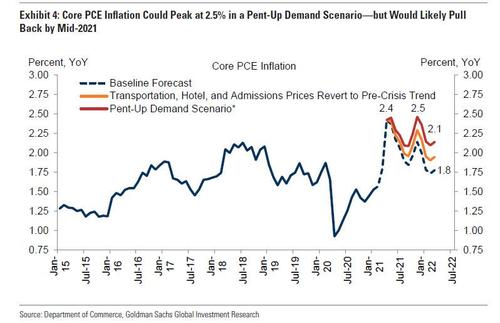

Admitting that price pressures have surged in recent weeks, in its base case, the bank forecasts core PCE inflation peaking at just 2.4% in April—bolstered by the year-on-year comparison to the April 2020 lockdowns — and then end the year at 2.0%, to wit:

Our forecast of a 0.5pp increase in core inflation between January and December is underpinned by a rebound in services categories, particularly those that underperformed last year due to the coronacrisis (see Exhibit 1). We also forecast normalization in apparel prices and a modest pickup in shelter inflation, which more than offsets the drag from diminished fiscal support to healthcare providers that has temporarily boosted inflation in that category.

But, Goldman then asks rhetorically, how high could core inflation rise if the bank is wrong about the shape of the rebound and if mass vaccination lead to an even more dramatic surge in demand for virus-sensitive services, reflecting pent-up demand and elevated savings during the crisis?

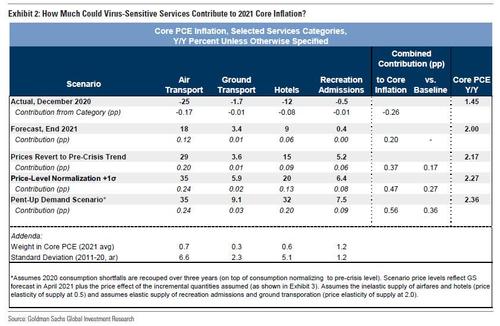

It then proceeds to estimate the possible inflation effects across four key categories for which consumption and prices fell significantly during the pandemic: air transportation, ground transportation (including taxis and ride sharing), hotels, and recreation admissions (including gyms, concerts, and amusement parks.

The bank notes that in its standing forecast (rows 3-4 of Exhibit 2), these four categories contributed +0.20% to year-on-year core inflation at the end of 2021, compared to a -0.26% contribution in December 2020 (rows 1-2). To capture the coming economic overheating, Goldman simulates alternative 2021 inflation contributions from these categories under three scenarios.

- In the first scenario (rows 5-6), GS economists assume price levels fully return to the pre-crisis trend by the end of this year. This would imply 29% year-on-year growth in airfares at end-2021, for example. Across these four categories, such a normalization would contribute +0.37% to year-end core PCE inflation, implying 2.17% in December 2021—or 0.17% upside to the bank's base case forecast.

- In our second scenario, the bank considers a 1-standard-deviation overshoot of the pre-crisis trend in these categories. Other things equal, this would produce 2.27% core PCE inflation at the end of this year.

- The third and final scenario looks at what if mass vaccination and pent-up demand lead to a boom in travel and recreation consumption later this year. Here Goldman assumes that consumption in these categories overshoots trend by enough to recoup the 2020 shortfalls over three years (2021-2023): "for example, imagine a family that attended three concerts in 2019. After forgoing entirely in 2020, they attend four concerts per year starting in 2021. We then convert these quantity changes into price outcomes based on a price elasticity assumption—the slope of the supply curve for each industry at these output levels." On this basis and as shown in the final scenario of the chart below (rows 9-10), these four categories would contribute 0.56% to core PCE inflation in December 2021, producing 2.36% core PCE inflation (0.36% above baseline)."

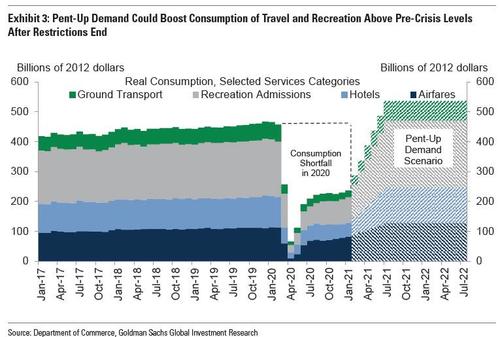

A visual summary of this third "pent up" scenario is shown below:

The next chart summarizes the range of core inflation outcomes in these upside scenarios. Relative to Goldman's baseline forecast, a pent-up demand scenario could lead core PCE inflation back to around 2.5% by Q4—before falling back to the low-2% in the first half of 2022 as the contribution from these categories normalizes (the bank says that it doubts airfares will rise by 30%+ for multiple consecutive years, although if there is a new fiscal stimulus every 3 months who knows...).

Which brings us to the $64 trillion question: how would the Fed view such a sudden and sharp inflation pickup?

Here even Goldman admits that several months of mid-2% core PCE inflation in late 2021 — at a time when unemployment is back around 4.5% based on Goldman's estimates — "would increase the odds of tapering asset purchases in late 2021, a bit earlier than we expect." But beyond that, Fed officials have already indicated that they would likely downplay the transient effects of a post-pandemic demand surge. To justify this view, Goldman reminds us of Powell's January press conference in which he said "Base effects... will pass. There's also the possibility [of] a burst of spending that could also create some upward pressure on inflation. We would see that as something likely to be transient and not to be very large... The way we would react is, we're going to be patient."

In other words, while ED markets have priced in nearly one full percent of rate hikes between 2022 and 2024...

... the Fed continues to believe that any inflation burst will be transitory and will not be a catalyst to hike rates (a position perfectly explained with the Fed's recently adopted revised Avg Inflation Targeting posture).

The jury is till out on who is right - markets and inflation expectations - or the Fed, but one thing is certain: one of the two will be very very wrong.

Commenti

Posta un commento