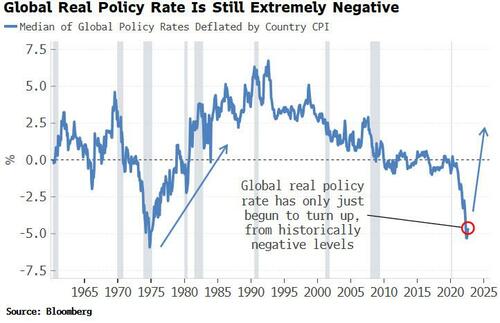

Don't let the cacophony of central-bank rate-hike announcements mislead you: global policy settings are still historically loose. Monetary policy has room to tighten much more significantly, leaving asset prices exposed to further, potentially material, downside.

This week the Riksbank in Sweden unexpectedly hiked 100bps, on Wednesday the Fed delivered its fifth consecutive rate increase, while the Philippines, Indonesia, Switzerland, Norway, South Africa and the UK are all expected to lift rates today.

Yet despite this flurry of policy tightening, the Global Policy Rate – the median central-bank rate of the major EM and DM countries around the world – is only 3%. This rate was more than 5% before the Lehman crisis, and 15% in the early 1980s.

But it's the inflation-adjusted version of this measure that's the real (pun intended) eye opener: the Global Real Policy Rate is very negative and still close to its historical lows. It has only recently begun to turn up, and has a long way to go to get back to zero - let alone move into restrictive territory

This has ominous implications for inflation and risk assets. If central banks get cold feet and stop hiking while the real policy rate is still firmly negative, then there is a high chance that the inflation fire will not have been fully put out. Eventually it will re-ignite, and even higher rates would be then be needed.

But that would open up a glorious window of opportunity for risk assets to outperform. Equities would fly, led by growth stocks; bond yields would fall; and the dollar would sell off. This trend would continue until it became apparent that inflation was reviving, and monetary policy was about to become very restrictive again.

The other possibility is that the hawkish central-banker hype is true, and Powell, Lagarde et al hike until the global real rate is positive, and then, channeling their inner Volcker, hike some more just to make sure.

If they do, then risk assets' and economies' travails are just getting started. Stocks would have much further to fall, front-end yields would have more to rise, and yield curves would have ample room to invert more – perhaps hyper-invert in the 2s10s case. (I don't buy that central banks will follow through on this purported hawkishness – it's easy to talk the talk when unemployment rates are rock bottom and widespread economic pain has yet to be felt).

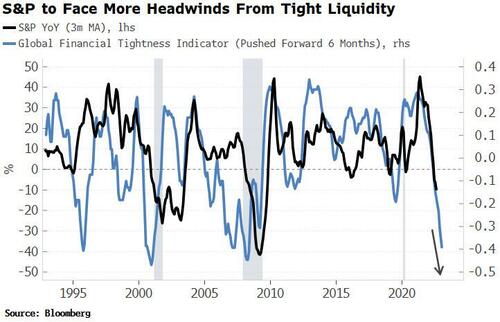

Either way, what is undeniable is that global monetary conditions are already tight, and that stocks and other risk assets are prone to more weakness. The Global Financial Tightness Indicator is a diffusion index of central-bank rate-hikes and other measures of credit and liquidity constriction. It has fallen sharply over the last year and shows that equities face more downside in the coming months.

Most disconsolately for the bulls, there is no sign yet that liquidity – one of the best medium-term indicators of equity performance – is about to turn up. It will be exceedingly difficult for stocks to make a sustainable rally while global liquidity remains so tight.

Furthermore, there's no light at the end of the tunnel. The chart below shows that the Advance Global Tightness Indicator - designed to give a lead on the Global Tightness Indicator and based on central-bank rate-hike expectations - continues to fall, meaning global liquidity will remain low and trending down over at least the next 3-6 months.

At Jackson Hole, Powell signaled the Fed would raise rates, and keep them high for an extended period. This strategy, if adopted by other central banks, will keep global financial conditions very tight with little chance of a near-term reprieve, and condemn equities and bonds to a protracted bear market.

Don't let the availability heuristic of the flurry of recent rate hikes fool you: history shows we are far from the potential peak of global monetary tightness. Considerable caution in markets continues to be well advised

Commenti

Posta un commento