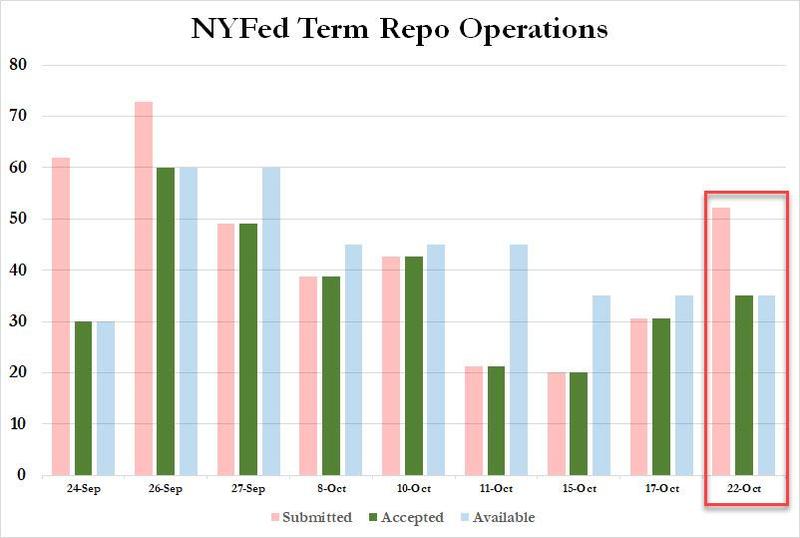

Actually, the big squeeze that began in September never went away; but repo auctions last week looked worse than ever, in spite of the Fed's launching of QE4ever. With a new $60 billion a month in permanent re-inflation of money supply pouring back into the economy now, the Fed still has found itself back to where it began in September with its repo operations becoming hugely oversubscribed, meaning it has more takers than what it is offering to give. Dealers submitted $52 billion in securities for two-week "loans" of new temporary money this past week against the Fed's offer to do $35B worth.

The story of the Fed's two-week term repos now looks like this:

Zero Hedge

Zero Hedge

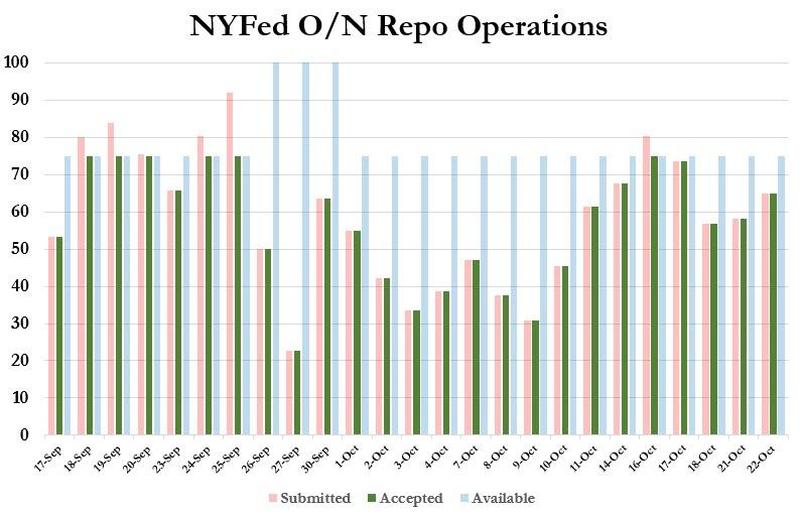

They're going back up to where they were. Meanwhile, overnight repos, set by the Fed with a cap of $75 billion per day, also went up in takers from $58 billion on Tuesday morning to $64 billion on Wednesday. That story, also not making any progress, looks like this:

Z.H.

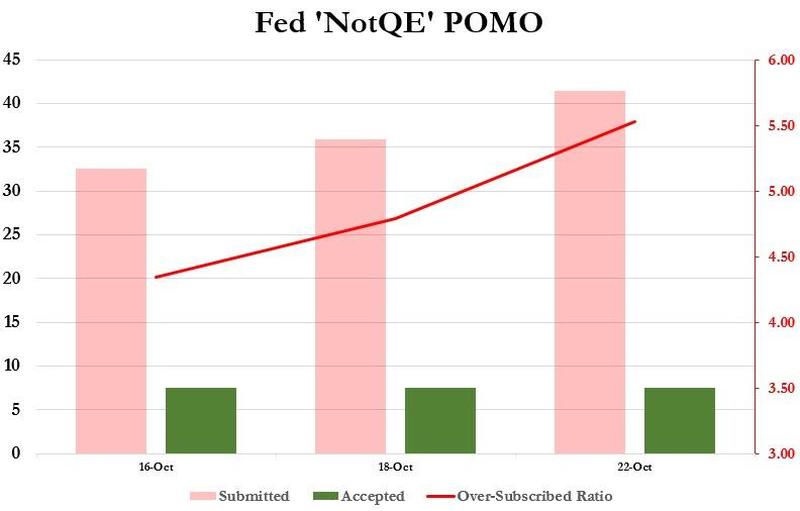

Z.H.Going back up to where it was. Meanwhile, the Fed's third round of its $60-billion per month (in issuances of $7 billion every few days) in permanent money creation, looked like this:

Z.H.

Z.H.Oh, but that's still not the end of it. You think I've been exaggerating how badly the Fed is failing. Well, it just got even worse -- much worse! The Fed announced this week it is increasing its overnight repos from $75 billion a shot to $120 billion!

Consistent with the most recent FOMC directive, to ensure that the supply of reserves remains ample even during periods of sharp increases in non-reserve liabilities, and to mitigate the risk of money market pressures that could adversely affect policy implementation, the amount offered in overnight repo operations will increase to at least $120 billion starting Thursday, October 24, 2019.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

So much for progress. Not to worry, though. All this demand for new money by banks is probably just due to a one-off surge this time in candy sales for Halloween, this being the spooky month for October surprises in financial markets.

If "the economy is still basically strong" as we continue to hear from the Trump administration and the Fed, why the increasingly desperate scramble for new money by banks everywhere? The Fed leaped back from tightening the financial system to full-on easing, and the ECB never even attempted tightening and has jumped back do doing €20 billion a month in QE. If you think we're getting off this QE merry go round before it flies off its axis, dream on.

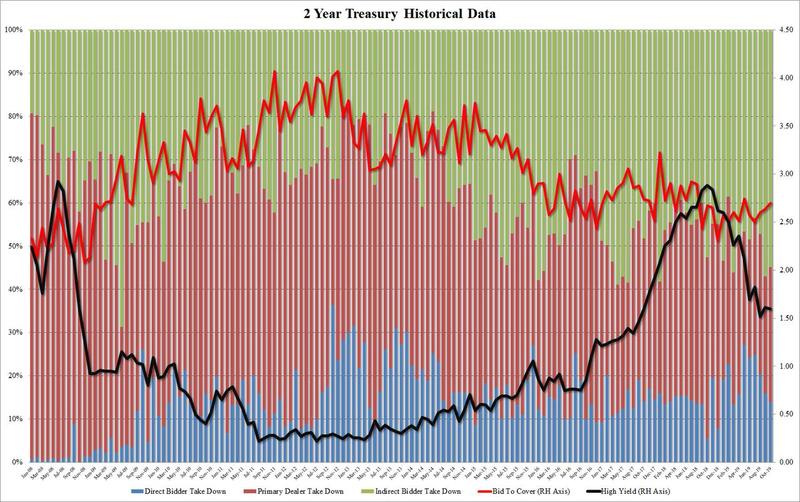

We now know for certain the repo crisis had nothing to do with end-of-quarter tax transactions, in that we are far past those, yet the crisis keeps growing worse. It grows worse no matter how much money the Fed pours into it. It doesn't appear it had anything to do with massive government bond issuances either, as those have found plenty of bids the entire time.

As you can see from the latest auction results, treasury yields continue to enjoy a easy ride with yields drifting nicely downhill:

How bad are central-bank troubles?

The seeming inability to get their economies going and to keep their member banks satisfied with cash might cause one to wonder how deeply are the central banks in trouble. The UN Secretary General put it this way:

In remarks to the International Monetary and Financial Committee, the UN chief said that "during tense and testing times" he continued to "fear the possiblity of a Great Fracture – with the two largest economies splitting the globe in two – each with its own dominant currency, trade and financial rules…. We must do everything possible to avert this…and maintain a universal economy.

UN News

OK. That sounds like it could be severe. This whole central-bank desperation for a larger answer is the stuff my Patron Posts are made of. So, I find the UN chief's stark encapsulation of this problem interesting, and he is far from the only one expressing things in such dire terms.

Consulting firm McKinsey & Co has reported that it believes more than half of the banks in the world are in perilous enough conditions that they could go down in the next global recession. Half! More than half!

"We believe we're in the late economic cycle and banks need to make bold moves nowbecause they are not in great shape," Kausik Rajgopal, a senior partner at McKinsey, said in an interview. "In the late cycle, nobody can afford to rest on their laurels…." In its report, the firm said banks risk "becoming footnotes to history."

Bloomberg

(McKinsey recommends banks make up for lost time in taking their money high-tech (digital) before competition from startups turns banks into dinosaurs.)

OK. That sounds dire, too. "Footnotes of history." But these stark notes don't stop there either. Let's move along to the former head of the Bank of England — the former chief of good ol' Pound Sterling — who is now free to speak his mind:

The world is sleepwalking towards a fresh economic and financial crisis that will have devastating consequences for the democratic market system, according to the former Bank of England governor Mervyn King…. King said the resistance to new thinking meant a repeat of the chaos of the 2008-09 period was looming…. He added that the US would suffer a "financial armageddon" if its central bank – the Federal Reserve – lacked the necessary firepower to combat another episode similar to the sub-prime mortgage sell-off…. King said the world economy was stuck in a low growth trap and that the recovery from the slump of 2008-09 was weaker than that after the Great Depression.… King said it was time for the Federal Reserve and other central banks to begin talks behind closed doors with politicians to make legislators aware of how vulnerable they would be in the event of another crisis.

The Guardian

Pretty stark words for a former bank head governor of the former imperial currency. These Fed-head types are not known for overstatement, and the British, are chief of understatement. It's not me, at this point, using terms like "Armageddon, crisis, devastating, chaos, Great Depression;" it's an establishment banker of one of the world's most august and conservative central banks!

If that doesn't sound like central bankers are running scared, then I don't know what it would take to sound like that. So, I see the present situation as one where the Fed is shoving familiar props under the sagging recovery as rapidly as it can while its colleagues and advisors warn — as has been said here for years would prove to be the case at this junction — that the old tricks just aren't going to be enough to work this time if the economy runs down into full-blown recession.

And that is why it is QE4ever

Or, at least, QE until a new banking masterplan is fully concocted and presented as the world's financial salvation from Armageddon.

Given how rapidly QE4ever is proving inadequate to the current needs and how everything the Fed has tried since its troubles began in September, who can believe QE4ever won't be getting its first increase before the end of the year? That's what makes it QE4ever — the longer it goes, the higher it goes.

As I noted in my last Post, at this point …

The Fed is really just chasing interest where markets are taking it. The best it can do at this point is pretend to have control in order to try to hold its currency stable.

Now that we are back to aiming for the zero bound in interest, does anyone want to venture where the bottom is once you go below zero on a race to find the final tier of sucker buyers, seeking speculative profits from rising bond prices (falling bond yields)? How deep can we go before the sides of the hole simply collapse in on us? Where do the bottom feeders feed when there is no more bottom?

No one knows because no one on earth has ever been here before — not to this depth and this breadth across the entire world with over $17 trillion in negative-rate securities. Nothing even remotely like this has ever happened in human history.

Even Howard Marks, cofounder of Oaktree Capital Management, when asked to explain negative yields, wrote,

I don't know anything about them.

S.Alpha

He went on to say, Nobody knows anything about negative rates – not really, anyway. Marks went on to ponder,

How will the markets value businesses that hold cash versus those that are deep in debt?

Which raises the question, "How do things change when negative rates effectively convert liabilities into assets?" Or, as Marks put it,

If having negative-yield debt outstanding becomes a source of income, will levered companies be considered more creditworthy?

In other words, if a corporation can make money just by issuing bonds, why not issue more of them and then more still?

Marks concludes,

I'm convinced that no one should be categorical about how to deal with a mystery like this in such unprecedented and confusing circumstances.

Or, as I asked in that Post I mentioned, which laid out the viral wackiness of this financial Wonderland,

What could possibly go wrong with turning an entire realm of national debt into a speculatively priced Ponzi scheme?

What could go wrong with central banks becoming the chief clown organizers of this spiraling debt scheme? And, yet, the world is filled with people who want to keep believing in it.

Clearly, the lift from QE is as gone as I said it would be when QE4ever finally began. Central banks are now clamoring to save the world from the debt monsters of their own creation, and their member banks are devouring the new cash fodder faster than their central masters are willing to create it, but it is doubtful that any of it will do anything of lasting value. Heck, they can't even seem at this point to do anything of temporary value!

As my Post continued,

With everyone in the decision-making corridors of all the governments in this world hell-bent on supercharged debt expansion, central banks will be increasingly pressed to finance those debts, just as the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank recently sprinted back into doing after a brief hiatus (with the Fed being the only bank that ever dared to try — quite unsuccessfully — to roll back its previous assumption of government debt).

The Fed is now permanently on a course of monetizing a debt that is now set to grow forever at a rate of, at least, $1.2 trillion a year — an annual deficit that is equal to the entire accumulated US debt from the founding of the United States to the end of the first term of President Ronald Reagan. With the deficit adding that much every year, the Fed is trapped into perpetual quantitative easing just to add enough money supply to cover the government's rapidly expanding interest payments and keep its rates pressured down.

Why I've said all along it will never work

Eric Basmajian of EPB Macro Research explains how QE starts to fail to work, including how, as I have explained many times, Fed policy has a long lag time before it changes the economy:

As central banks ease monetary policy and lower interest rates, within several months, money supply growth often starts to accelerate, fueled by easier conditions, the first sign that economic growth may start to inflect higher. Changes in money supply growth can often lead inflections in more commonly followed economic data by over a year.

S. Alpha

Stated the other way around, it takes several months from the time the Fed starts lowering interest rates until the first metrics of actual monetary supply begin to appreciably rise. That's just the first hint that some lift is about to from. As he goes on to say, it can take more than a year, however, before that increase in money supply is followed by an improvement in general economic data. It takes half a year to a year or even more before the Fed's changes in interest rates start to really change the general economy, and that is why I've said all along the Fed will be, as it always has been, coming in with too little too late to prevent the demise of its recovery.

The Fed creates money through debt, particularly the national debt, so over time QE becomes less effective — the Law of Demising Returns that I have often said will come into play. Basmajian puts it this way:

As economies become more indebted, central bank policy loses its efficacy in a concept often referred to as "pushing on a string." Central banks are trying to ease conditions, but some monetary aggregates are unresponsive.

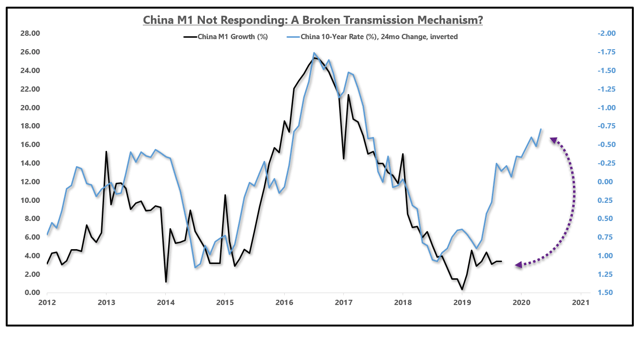

And then he presents a picture that really clarifies just how much that is true. In the following graph, you can see how whenever China has increased its monetary stimulus by getting interest down on its 10-year bond (inverted in the graph), money supply has responded by growing … until now:

S. Alpha

S. Alpha

This time, China is pushing the accelerator to the floor, but money growth is barely responding.

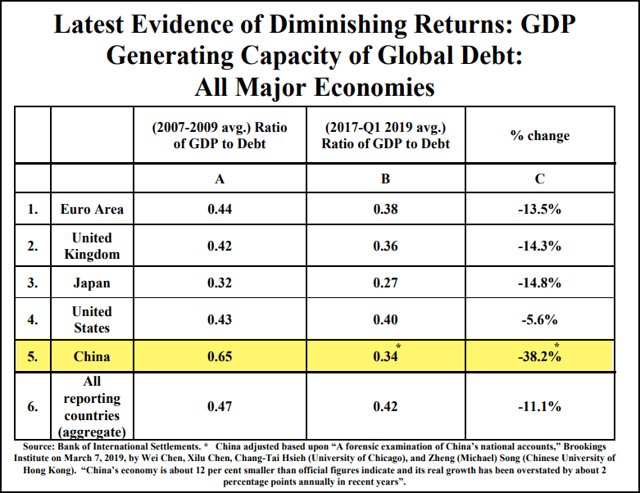

The effectiveness of using national debt (fiscal stimulus) to expand global economies is also shrinking, including in the US:

We all know this is how the Law of Diminishing Returns works with everything — less and less bang for the buck. We ignore that reality to our own peril. China is experiencing it the most now because its economy is young in terms of it recent successes and has been expanding the fastest, but all economies have become slower to respond to stimulus.

Basmajian notes,

As the GDP-to-Debt table above shows, the efficacy of global debt [to create economic expansion] has declined by about 11% over the past ten years. While central banks scrambleto ease monetary policy enough to avoid a recession, their job has become increasingly difficult with less effective tools.

This is why we hear central bankers like Mervyn King laying out their concerns that the old tools of central bankers are not going to be effective this time around. They are behind the curve on new ideas. The old path of quantitative easing didn't lift the economy to a new plateau; the next will have even less lift, possibly not even enough to keep it from endlessly sinking.

So, we've landed where I've said we would land, and we now get to watch how the failed plans of our central banksters play out. Will it be catastrophically like an animal falling off a cliff or slowly, like an animal sinking into the La Brea Tar Pits? I don't know the answer to that because we've come into that place we've never been before. "Catastrophic" and "Amarageddon" are the words bankers and analysts are using for it, but whether that comes about by sudden heart attack or slow strangulation, who can know? That it is coming about or is in severe risk of coming about, those in high banking places seem to agree — those, at least, who are now free to speak. The ones actually in charge dare not say so.

Commenti

Posta un commento