In this issue of The Institutional Risk, we feature a timely conversation with Dr. George Selgin, senior fellow and director of the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute and Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Georgia. He is the author of a number of books, including Floored! How a Misguided Fed Experiment Deepened and Prolonged the Great Recession (The Cato Institute, 2018) and writes frequently on monetary policy, payments and related topics for Alt-M. We spoke to Dr. Selgin last week from his office in Washington.

The IRA: George, thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. Let's start with the snafu in the world of repurchase agreements and short-term money markets and then move to the equally important question of payments. First thing, how do you explain the liquidity problems seen in the REPO market over the past year to ordinary citizens and particularly members of Congress? More important, how do you link the policy narrative coming from the Federal Open Market Committee with what the Fed is actually doing in the markets? The two often seem disconnected.

Selgin: Those are some big questions. You start by observing that for some decades now the Fed like other central banks has insisted that its task is to regulate short-term interest rates. So, when interest rates do something that the Fed has not planned for them to do, that's a problem. If the Fed isn't able to control interest rates, then what is it doing and what is it able to do? I'd start with that premise, that the Fed is supposed to be able to keep interest rates on the desired target or target range, but in fact has been having trouble doing so. It had trouble keeping rates in line in September and it may soon have trouble doing so again.

The IRA: Well, investors may not cooperate. The whole idea of targeting interest rates, as you noted in your book "Floored," essentially amounts to the nationalization of a heretofore private financial market. But do continue.

Selgin: The second point to make is that under the post 2008 system, banks are supposed to have all kinds of liquidity; they should have so much liquidity that they never have to resort to borrowing from other banks to cover shortfalls in reserves. But things haven't turned out that way. It was the desire of some banks to cover reserve shortfalls, for example, plus the unwillingness of other banks to lend was the proximate cause of problems in September and may become one again.

The IRA: Indeed. Isn't it remarkable to see Fed Governor Randal Quarles at the Fed and Zoltan Pozsar at Credit Suisse (CS) each put various pieces of the puzzle forward for our consideration, but no one really talks about your point namely the idiosyncratic behavior of individual banks. Wells Fargo (WFC), for example, has 15% more liquidity than it needs to fulfill the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and other tests. JPMorgan Chase (JPM) likewise is no longer providing liquidity to the markets as year-end approaches. Trillions of dollars in liquidity is essentially out of the market.

Selgin: That's right. There are two ways to understand why reserves ended up in short supply. One which the Fed has tended to emphasize is that the Fed miscalculated how many reserves would be required to keep the system flush, particularly in making plans for reducing the size of the balance sheet starting in October 2017. Consequently, it seems to have overdone things a little bit.

The IRA: Ya think? Do our colleagues in the Fed system appreciate just how close we came to running the ship aground? Last December particularly?

Selgin: I think they do now! What they don't appreciate enough, but are coming around to appreciating, is that the problem is not simply that there are not enough total reserves in the system, but that those reserves are concentrated in a few large banks, including Wells but also others. And they failed to reckon with the fact that, even though these banks on paper had sufficient liquidity to meet the LCR rule and other liquidity requirements, in fact they did not feel comfortable lending out what seems to be a surfeit of reserves—not even in response to high rates and for short periods.

The IRA: Or even to their own people. We reported on one case where the bank side of a certain money center essentially told the capital markets desk of the same bank that they had to pay those elevated market rates.

Selgin: There are subtle regulatory constraints, including some rules that are unwritten, or written as it were on the margins of the regulations. Those rules are constraining banks more than the Fed and other regulatory authorities, or the bankers' themselves, expected. The Fed is learning that the banks are interpreting the rules in such as way that they really need to keep more liquidity than was once thought necessary.

The IRA: To that point, isn't the "island of liquidity" notion adopted by the Fed and other prudential regulators, where a large money center bank need not transact with the market for 30 days or more, a little extreme? It reminds us of the ridiculous requirement in the Volcker Rule that banks not trade around their treasury portfolios, a requirement that killed liquidity in the bond market. The cumulative effect of all of these rules is to reduce market liquidity.

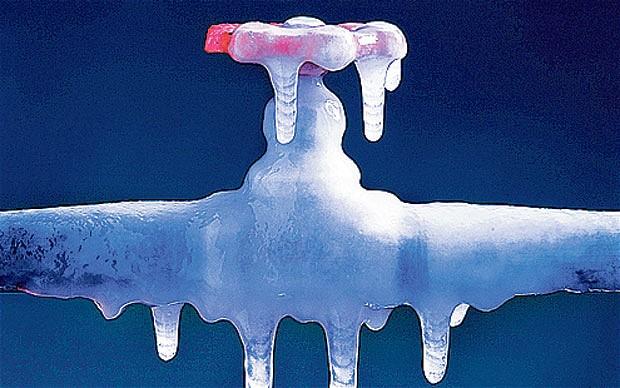

Selgin: I think it probably is a little excessive. After every major financial crisis, the tendency isn't just for the regulatory authorities to shut the barn gate after the horses have bolted. They slam the gate shut so tight that you can't get new horses out for exercise. That's what's happened since the 2008 crisis; that the regulatory pendulum has swung too far in the direction of stringency. Now we have a system where in theory there are plenty of reserves, way more than 2008, but various requirements, some interacting in subtle ways, mean that all of that liquidity is frozen. It does not move around that way it did pre-2008. So, you have large amounts of reserves that can't go where they're needed. As I said in a Tweet recently, something can be liquid or it can be frozen. Today the liquid reserves of the banking system aren't really liquid because they're frozen.

The IRA: Hasn't this been the approach all along, going back to the 1990s to reduce liquidity via regulation? In the 1990s, when the SEC changed Rule 2a-7 and essentially made it impossible for nonbanks to sell pass through securities to money market funds, we created a monopoly on short-term funding for banks. The regulators keep taking functionality out of the money markets, then they wonder why there is a liquidity problem to your point.

Selgin: That's right. But you can go back a lot further than the 1990s. You can go back to the 19th century, when countries, including the United States, started to experiment with various types of reserve requirements. What most nations eventually discovered is that, when you make these requirements strict enough, the reserves simply don't do what you want them to do. That is, the banks can't use them when it would benefit them and the economy for them to do so. Uniquely among industrialized nations, the United States still has nominally fixed reserve requirements for banks. Most other nations got smart and dispensed with them years ago. They came around to the view that, while liquidity is very important, rigidly enforced reserve requirements did not make banks more liquid. If anything, they made them less liquid. History now seems to be repeating itself in the US, where Basel and other rules have made banks less rather than more liquid.

The IRA: Based upon the Fed's clumsy handling of the liquidity issue, we'll not hold our breath waiting for a comprehensive fix of the problem you describe. Moving now from the money markets to payments, let's talk about why the Fed seems intent upon creating a new payments system to compete with the Clearing House Association. The Fed today enforces a monopoly on payments reserved exclusively for insured depository institutions, but now the central bank seemingly wants to compete with the private sector.

Selgin: It's generally true that if you want to have innovation in payments, you must have a system that interacts with the established banking system payments network. That is the big one. There are other networks out there that could potentially support important payments systems, such as Facebook (FB) with its proposed Libra exchange medium. Still, the banking system has a huge advantage when it comes to dollar-based payments, and when it comes to dollar payments would-be non-bank innovators must be able to tap into the bank-based payments network. This creates a huge problem for non-banks that want to get a piece of the action in payments without needing the cooperation of a potential rival. That's one challenge. The other challenge for innovation is that banks themselves have to work with the Fed. The big challenge for banks is that the Fed can itself compete with their efforts to expedite payments. Everybody is talking about FedNow, the Fed's plan for a new real-time retail payments system. FedNow will compete with RTP, a private real-time payments network created by The Clearing House (TCH). which has been up and running since 2017. Another challenge is getting the Fed to improve those portions of the dollar payments system that it monopolizes upon which other payments service providers depend. This is really the elephant in the room when it comes to payments.

The IRA: Well, the future of payments is FedNow, right? The Fed is a GSE just like Ginnie Mae and the Federal Home Loan Banks. No private entity, even a big bank, can compete with a GSE.

Selgin: Not easily. And the Fed regulates the banks behind RTP, the system FedNow will compete with TCH.. Does competition from the Fed help or hurt consumers of payments services? There is a fundamental conflict of interest for the Fed to be competing with the banks that it regulates. But the bigger issue is not FedNow or the huge amounts of money that the Fed is likely to spend creating its alternative instant payments system. It's what the Fed is not planning to do. There needs to be more discussion of how the Fed can improve the payment services it already provides, especially by extending the operating hours of its wholesale payments services, FedWire and the National Settlement Service. By enhancing those systems it would help to support private-system payment system innovations, like RTP. Instead of competing with RTP, the Fed would do more good by improving the speed and efficiency of the wholesale payment services upon which all existing non-cash retail dollar payments depend. All of the payments systems that exist or are contemplated depend upon one or both of the Fed's wholesale payment services.

The IRA: So how should the Fed proceed?

Selgin: The entire legacy payments system sits atop the FedWire and the National Settlement Service foundation. All ACH payments, all check payments, are settled using one or both of those services. Why is it that ordinary payments between two US banks can take days to clear? Hold onto your hat: FedWire and the National Settlement Service are not open on weekends or holidays. In fact, the business-day hours are so limited as to substantially reduce the extent to which ACH payments can be completed on a single day.. Simply extending those services' hours, including keeping them open on weekends and holidays, would enormously enhance the speed and efficiency of traditional payments. Just keeping the system open another 30 minutes each weekday would make a great difference. Instead of working on a controversial, expensive and possibly redundant FedNow system, why doesn't the Fed first improve its existing, core payments services?

The IRA: And who knows, accelerating the velocity of payments might even have economic benefits! Imagine that! Thanks George.

Commenti

Posta un commento