As inflation talk escalates in the financial markets even with chances of QE tapering in the wings perhaps this fall, it is worth checking to see if history is repeating itself with regard to the 1970's inflationary debacle. For us; the lyrics are different, the musicians are new, but the melody is the same. We found a twitter thread by Sid Prabhu in which he reads through and comments on a 1979 paper entitled "The Anguish of Central Banking".

The Lecture That Scared Volcker Straight*

*a reference to the documentary "Scared Straight" in which hardened criminals scare youth offenders off the "crooked path of crime" so they don't become recidivist criminals.

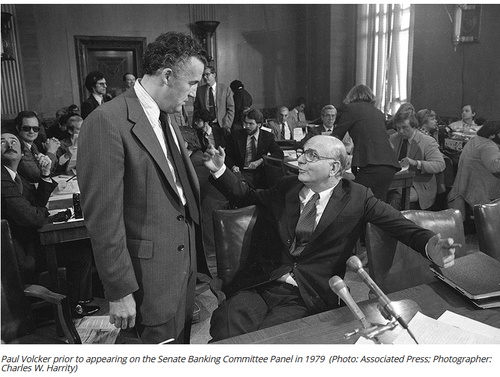

Arthur F. Burns, was Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System from 1970 to 1978. The paper referenced and included at bottom is a reprint of the address Dr Burns gave as the sixteenth Per Jacobsson Lecture, at Belgrade, Yugoslavia, on September 30, 1979. In October 1979, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker announced new measures by the Federal Open Market Committee aimed at reining in the inflation that had afflicted the US economy for several years.

[EDIT: It appears that Volcker was in fact influenced by Dr. Burns lecture based on the timing of the turnaround and rate hike. What is more likely is they had discussed what needed to be done and Burns was the person to deliver the message. Volcker was already prepared to take the actions needed. Burns in effect gave Volcker cover to do what had to be done. Look for that again in the current situation. - VBL]

In his lecture, Dr. Burns goes through some of the reasons, drivers, and likely explanations why things got out of hand.

Spooky Parallels

(Then- NOW):

- Philosophical and political changes - MMT, ESG, authoritarian forms of capitalism, definitions of words like "real" and "fact"in flux

- Desire for a more interventionist govt - Same as today

- Unevenly spread prosperity - Caused in no small part by previous Fed Policies for the past 50 years

- Substantial societal tensions - Witness the riots continuing now

- Reflexive embedded societal expectations- Stimulus will likely not end all at once

- Overwhelming goal of full employment - Powell has said almost the same thing overtly telling us inflation is the lesser evil. Even calling it a mandate itself at one point

- Environmental policies added to the inflation.- Do we think ESG is free? Does copper grow on trees?

- Entitlements diminished the work ethic- Stimulus makes it easier for people to wait

- Fed had tools to stop the inflation, but chose not to use them because it had been caught up in the social movements of the day - Powell et al have stated mandates outside their real ones like social justice and climate change as their priorities. This just underlines their concern with political optics rather than their real job.. and worse. Their polices do the exact opposite of the changes that need to be effected even while they pay lip service

- Fed is beholden to Congress, how could it stand in they way of societal changes that Congress was attempting to enact - Which is why we see the Fed echo current congress mandates

- Understand what the appropriate level of "full employment" was - As it is now, where they do not know what people are trained to do in the accelerated virtual economy with a rapidly changing demographic

- Central Banks can't stop politically driven inflation. They have the tools, but not the will - They are politically driven now as well. What they say is not what they do, ever.

- Inflation was fed by high unemployment, deficits, money creation - All 3 boxes checked.

- Ultimately led to a conservative political movement - As the Reagan revolution in the 1980s happened, so in next election we may see a bigger conservative backlash

After each italicized comment by Sid is the section to which he references as source of the comment. All emphasis ours- VBL

Fascinating paper by Arthur Burns - the 1970s Chairman of the Federal Reserve explaining what happened. Feels a lot like today...Philosophical and political changes in the US post Depression and WW2 caused the inflationary environment

I have no quarrel with analyses of this type. They are distinctly helpful in explaining the American inflation and, with changes here and there, that in other nations also. At the same time, I believe that such analyses overlook a more fundamental factor: the persistent inflationary bias that has emerged from the philosophic and political currents that have been transforming economic life in the United States and else where since the 1930s. The essence of the unique inflation of our times and the reason central bankers have been ineffective in dealing with it can be understood only in terms of those currents of thought and the political environment they have created.

Much like the post GFC period, there was a desire for a more interventionist govt policy to help foster employment.

This tradition of individualism was shattered by the cataclysmic events of the 1930s and 1940s. The breakdown of economic order during the Great Depression was unprecedented in its scale and scope, and it strained the precept of selfreliance beyond the breaking point. With onequarter of the labor force unemployed, personal courage and moral stamina could guarantee neither a job nor a livelihood. Succor finally came through a political idea that was novel to a majority of the American people but compelling nonetheless—namely, that the federal government had a far larger responsibility in the economic sphere than it had hitherto assumed.

But the prosperity of the 60s was not evenly spread and there were substantial societal tensions.

But the rapid rise in national affluence did not create a mood of contentment. On the contrary, the 1960s were years of social turmoil in the United States, as they were in other industrial democracies. In part, the unrest reflected discontent by blacks and other minorities with prevailing conditions of social discrimination and economic deprivation—a discontent that erupted during the "hot summers" of the middle 1960s in burning and looting. In part, the social unrest reflected growing feelings of injustice by or on behalf of other groups—the poor, the aged, the physically handicapped, ethnics, farmers, bluecollar workers, women, and so forth. In part, the unrest reflected a growing rejection by middleclass youth of prevailing institutions and cultural values. In part, it reflected the more or less sudden recognition by broad segments of the population

These tensions led to an even more interventionist govt.

In the innocence of the day, many Americans came to believe that all of the new or newly discovered ills of society should be addressed promptly by the federal government. And in the innocence of the day, the administration in office attempted to respond to the growing demands for social and economic reform while waging war in Vietnam on a rising scale [NOTE: This is why we are pulling out of the middle east wars now. Same behavior as post Vietnam. We cannot afford it anymore- VBL]. Under the rubric of the New Economics, a more activist policy was adopted for the purpose of increasing the rate of economic growth and reducing the level of unemployment. Under the rubrics of the New Frontier and the Great Society, broad-scale efforts were made to stitch up open seams in the fabric of affluence—inadequate or unequal education, housing, medical care, nutrition. Under the rubrics of civil rights and citizen participation, minorities and other disadvantaged groups were given political weapons to maintain, consolidate, and extend their gains. The interplay of governmental action and private demands had an internal dynamic that led to their concurrent escalation. When the government undertook in the mid-1960s to address such "unfinished tasks" as reducing frictional unemployment, eliminating poverty...

Which became reflexively embedded in societal expectations.

Once it was established that the key function of government was to solve problems and relieve hardships—not only for society at large but also for troubled industries, regions, occupations, or social groups—a great and growing body of problems and hardships became candidates for governmental solution. New techniques for bringing pressure on the Congress— and also on the state legislatures and other elected officials—were developed, refined, and exploited. The Congress responded by pouring out a broad stream of measures that involved government spending, special tax relief, or regulations mandating private spending. Every demonstration of a successful tactic in securing rights, establishing entitlements, or extracting other benefits from government led to new applications of that tactic. Various groups found a powerful ally in the federal courts, which repeatedly struck down legislative or administrative limitations on access to government benefits.

The overwhelming goal of policy was full employment

The pursuit of costly social reforms often went hand in hand with the pursuit of full employment. In fact, much of the expanding range of government spending was prompted by the commitment to full employment. Inflation came to be widely viewed as a temporary phenomenon—or, provided it remained mild, as an acceptable condition. "Maximum" or "full" employment, after all, had become the nation's major economic goal— not stability of the price level. That inflation ultimately brings on recession and otherwise nullifies many of the benefits sought through social legislation was largely ignored. Even conservative politicians and businessmen began echoing Keynesian teachings.

Well intentioned environmental policies added to the inflation.

...even in the face of accelerating inflation during 1977 and 1978. Also troublesome were the newer social regulations—those concerned with health, safety, and the environment—that kept multiplying during the 1970s. However laudable in purpose, much of this regulatory apparatus was conceived in haste and with little regard to the costs being imposed on producers. Substantial amounts of capital that might have gone into productivityenhancing investments by private industry were thus diverted into uses mandated by the regulators. Improvements in productivity were also slowed by the discouragement of business investment that resulted from the increasing burden of income and capital gains taxes. Progress in equipping the work force with new plant and equipment proceeded much less rapidly during the 1970s than during the 1950s or 1960s, and this shortfall contributed to the productivity slump and thus to the escalation of costs and prices.

Entitlements diminished the work ethic of the labor force.

Additional forces on the side of supply contributed to the inflationary bias. As the income maintenance programs established by government were liberalized, incentives to work tended to diminish. Some individuals, both young and old, found it agreeable to live much of the time off unemployment insurance, food stamps, and welfare checks—perhaps supplemented by intermittent jobs in an expanding underground economy. Even enterprising and ambitious individuals who sought permanent jobs could be more leisurely or more discriminating in their search when the government, besides pursuing a fullemployment policy, provided a protective income umbrella during jobless periods. In such an environment, employed workers could demand and often achieve longer vacations with pay and more frequent holidays and sick leave, besides enjoying coffee breaks and other social rites on the job. In such an environment, they could afford to reject a pay cut or a small wage increase when their employer pleaded serious financial difficulties. Thus the number of individuals counted as unemployed could rise even at times when job vacancies, wages, and the consumer price level were rising.

The Fed had tools to stop the inflation, but chose not to use them because it had been caught up in the social movements of the day.

Some industrial democracies, to be sure, have substantially independent central banks, and that is certainly the case in the United States. Viewed in the abstract, the Federal Reserve System had the power to abort the inflation at its incipient stage fifteen years ago or at any later point, and it has the power to end it today. At any time within that period, it could have restricted the money supply and created sufficient strains in financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay. It did not do so because the Federal Reserve was itself caught up in the philosophic and political currents that were transforming American life and culture.

Ultimately the Fed is beholden to Congress, how could it stand in they way of societal changes that Congress was attempting to enact?

The Employment Act of 1946 prescribes that "it is the continuing policy and responsibility of the Federal Government to . . . utilize all its plans, functions, and resources .. . to promote maximum employment." The Federal Reserve is subject to this provision of law, and that has limited its practical scope for restrictive actions—quite apart from the fact that some members of the Federal Reserve family had themselves been touched by the allurements of the New Economics. Every time the government moved to enlarge the flow of benefits to the population at large, or to this or that group, the assumption was implicit that monetary policy would somehow accommodate the action. A similar tacit assumption was embodied in every pricing decision or wage bargain arranged by private parties or the government. The fact that such actions could in combination be wholly incompatible with moderate rates of monetary expansion was seldom considered by those who initiated them, despite the frequent warnings by the Federal Reserve that new fires of inflation were being ignited. If the Federal Reserve then sought to create a monetary environment that fell seriously short of accommodating the upward pressures on prices that were being released or reinforced by governmental action, severe difficulties could be quickly produced in the economy. Not only that, the Federal Reserve would be frustrating the will of the Congress, to which it was responsible—a Congress that was intent on providing additional services to the electorate and on assuring that jobs and incomes were maintained, particularly in the short run.

Demographic changes in the workforce made it difficult to understand what the appropriate level of "full employment" was.

Even facts about current conditions are often subject to misinterpretation. Statistics on unemployment in the United States provide a good example. Even before World War II ended, some economists were trying to determine how much frictional and structural unemployment would exist when the demand for labor and the supply of labor were in balance; in other words, the rate of unemployment that would reflect a state of full employment. Before long, a broad consensus developed that an unemployment rate of about 4 percent corresponded to a practical condition of full employment, and that figure became enshrined in economic writing and policymaking. Conditions in labor markets, however, did not stand still

High inflation made real rates very negative, negating the impact of rate rises.

An "inflation premium" thus gets built into nominal interest rates. In principle, no matter how high the nominal interest rate may be, as long as it stays below or only slightly above the inflation rate, it very likely will have perverse effects on the economy; that is, it will run up costs of doing business but do little or nothing to restrain overall spending. In practice, since inflationary expectations, and therefore the real interest rates implied by any given nominal rate, vary among individuals, central bankers cannot be sure of the magnitude of the inflation premium that is built into nominal rates. In many countries, however, these rates have at times in recent years been so clearly below the ongoing inflation rate that one can hardly escape the impression that, however high or outrageous the nominal rates may appear to observers accustomed to judging them by a historical yardstick, they have utterly failed to accomplish the restraint that central bankers sought to achieve. In other words, inflation has often taken the sting out of interest rates— especially, as in the United States, where interest payments can be deducted for income tax purposes.

Ultimately Central Banks can't stop politically driven inflation. They have the tools, but not the will

My conclusion that it is illusory to expect central banks to put an end to the inflation that now afflicts the industrial democracies does not mean that central banks are incapable of stabilizing actions; it simply means that their practical capacity for curbing an inflation that is continually driven by political forces is very limited. Historically, central banks have helped to slow down the pace of economic activity at certain times and to stimulate economic activity at other times. They have also contributed to economic stability by serving as lenders of last resort or even going beyond that traditional function. During this decade alone, the Federal Reserve moved on at least two occasions to prevent financial crises that otherwise could easily have occurred.

Inflation was fed by high voluntary unemployment, deficits, money creation and a high savings rate that was drawn down, making it difficult to control.

Many economists now recognize that much of reported unemployment is voluntary, that curbing inflation and reducing involuntary unemployment are complementary rather than competitive goals, that persistent governmental deficits and excessive creation of money tend to feed the fires of inflation, that the high savings rate that usually prevails in the early stages of inflation is eventually succeeded by minimal savings, and that when this stage is reached it becomes very much harder to bring inflation under control.

Ultimately this all led to a conservative political movement that fought back against perceived excessive government intervention.

The intellectual ferment in the world's democracies is having its influence not only on businessmen and investors, but also on politicians, trade union leaders, and even housewives; for all of them have been learning from experience and from one another. In the United States, for example, people have come to feel in increasing numbers that much of the government spending sanctioned by their compassion and altruism was falling short of its objectives: that urban blight was continuing, that the quality of public schools was deteriorating, that crime and violence were increasing, that welfare cheating was still widespread, that collecting unemployment insurance was becoming a way of life for far too many—in short, that the relentless increases of government spending were not producing the social benefits expected from them and yet were adding to the taxes of hard-working people and to the already high prices they had to pay at the grocery store and everywhere else. In my judgment, such feelings of resentment and frustration are largely responsible for the conservative political trend that has developed of late in the United States. And I gather from the results of recent elections elsewhere that concern about inflation and disenchantment with socialist solutions are increasing also in other industrial countries. Fighting inflation is therefore being accorded a higher priority by policymakers in Europe and in much of the rest of the world

Ending the inflationary psychology required drastic therapy.

If the United States and other industrial countries are to make real headway in the fight against inflation it will first be necessary to rout inflationary psychology—that is, to make people feel that inflation can be, and probably will be, brought under control. Such a change in national psychology is not likely to be accomplished by marginal adjustments of public policy. In view of the strong and widespread expectations of inflation that prevail at present, I have therefore reluctantly come to believe that fairly drastic therapy will be needed to turn inflationary psychology around.

Feels like a lot of what is happening today. Even if its impossible to know where we are in the cycle, the secular environment has changed. The US stock market was flat from 1968-1982, while prices doubled, so a pretty bad time for investors.Post script to this - Volcker flew home early from this conference and started tightening the money supply within the next week.He also had a habit of cherry picking inflation numbers. The original excellent thread by Sid:

"community-adjusted inflation" https://t.co/iJ8lJ70x4g

— Sid Prabhu (@sidprabhu) May 17, 2021

Volcker raised the federal funds rate from 11.2% in 1979 to 20% in June of 1981. The unemployment rate became higher than 10% during this time as well. Volcker chose to enact a policy of preemptive restraint during the economic upturn which increased the real interest rates.

Commenti

Posta un commento