What is the U.S.'s greatest export? Banknotes. There is probably no other product for which the balance of trade is so tilted in the U.S.'s favour. No foreign bills circulate in the U.S., but U.S. bills are eagerly used all over the world.

According to the Federal Reserve, there are currently $1.74 trillion paper dollars in circulation. How many of these notes circulate in the U.S. and how many are used overseas?

Because banknotes cannot be tracked, this question is particularly difficult to answer. This blog post explores several approaches for determining the location of notes. These approaches offer a wide range of estimates, from as low as 40% of all currency being held outside of U.S. borders to as high as 72%.

The international demand for dollars

There are a number of reasons why foreigners demand U.S. dollars. A few nations including Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador are dollarized. They no longer have their own currency but are wholly dependent on U.S. dollar for trade. There is an even longer list of countries that are partially-dollarized. While Argentina, Angola, Cambodia, Nicaragua, and Russia each maintain local currencies, it is common for U.S. dollars to be used in a portion of their domestic transactions.

Nations tend to dollarize because they have experienced high domestic inflation. Because the purchasing power of dollars is much more reliable than that of a weak domestic currency, individuals and businesses develop a habit of using dollars for making transactions or hoarding wealth. Even years after the domestic inflation has been contained, this habit remains.

Dollars are also popular in the international drug trade. Criminals require secrecy, and by their nature banknotes are a privacy-preserving form of payment. Because U.S. dollars are so liquid, they have become the preferred medium for illicit international business dealings.

How do notes move overseas?

One of the main channels for banknote exports is via the official banking sector. Banks put in large orders for notes with the Federal Reserve and ship them to branch offices overseas or other foreign banks.

Retail flows are also large. Tourists leaving the U.S. will often bring U.S. currency with them, either changing it at foreign banks or spending it directly into circulation. Immigrants living in the U.S. who support family back home will often physically transport cash over the border or send it by mail.

Smuggling of illicitly earned cash is another channel by which notes leave the border. Finally, the U.S. government itself moves large amounts of cash overseas. For instance, it brought over 300 tonnes of paper dollars into Iraq to help fund the Iraq War.

No paper trail

It is very difficult to measure how many paper dollars are in circulation outside of U.S. borders. This is because currency lacks a paper trail. When notes pass from one person to the next, there is no need for the recipient to register their possession of the note, or for the issuer to validate the transfer. Which means there is no way to directly track where banknotes go.

Ruth Judson, an economist at the Federal Reserve, has spent almost 25 yeas trying to understand some of the mysteries of U.S. banknotes. Along with Richard Porter she has tried to get a handle on the amount of counterfeit U.S. currency in existence. More salient to this post, the duo have written three papers on the international demand of U.S. currency (1996, 2001, and 2004.) Prior to that, Porter published on the topic (1993). Judson has herself authored two more recent papers on dollars overseas (2012, 2017).

Look North

Over the years, Judson has used a number of methods to infer how many U.S. bills circulate overseas. Here is one of the simplest techniques. We already know exactly how many U.S. dollar notes there are globally as of June 2019: $1,738.3 trillion. We then need to generate a good guess about how much of this is held domestically. Once we have this number, we can subtract it from the total stock in order to arrive at foreign holdings.

But how can we determine how much currency is held domestically? Judson's trick is to assume that Americans are pretty much like their northern neighbours, Canadians. This is a fairly safe assumption. The two nations inhabit the same continent, have common traditions, and share similar wealth levels. It seems reasonable that Canadians and Americans prefer to hold the same amount of banknotes.

Unlike U.S. banknotes, Canadian banknotes do not circulate outside of Canadian borders. So almost all of the $90 billion or so in banknotes that the Bank of Canada has printed up as of June 2019 are held domestically. This gives a good indication of Canadians' taste for banknotes.

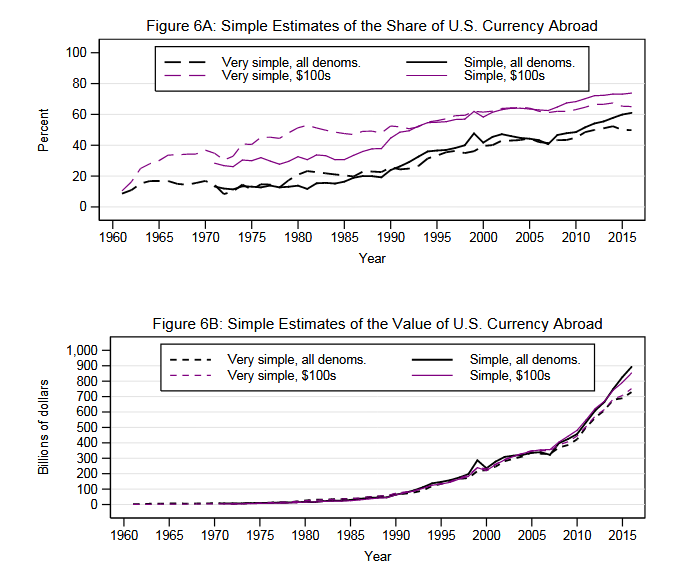

In her 2017 paper, Judson found that Canadians hold around 4% of nominal GDP in the form of currency. Based on the assumption that Americans hold the same ratio of notes-to-GDP as Canadians (and adjusting for Canada's slightly lower per capita income) Judson estimates that some $600 billion in U.S. currency was held domestically at the end of 2016. See the solid black line in chart 6B below.

U.S. banknotes overseas, computed using the Canadian note-to-GDP ratio as an indicator of U.S. demand. Source: Judson (2017).

Given that the Federal Reserve had issued about $1.5 trillion in currency by that time, the remaining $900 billion in notes must have been held overseas. This amounted to about 60% of all American banknotes (see solid black line above in chart 6A). Judson further estimates that around 70% of all $100 bills are held overseas.

The Christmas note spike

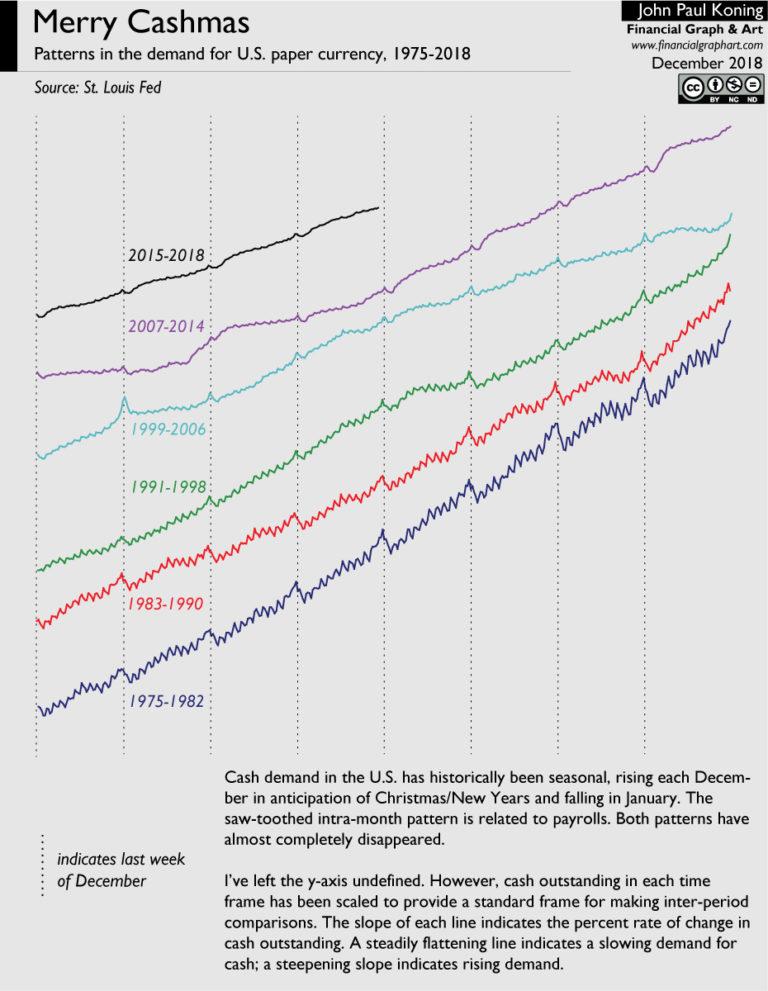

Another trick that Judson uses to suss out foreign demand is to take advantage of U.S. and Canadian seasonal spikes in currency usage, like Christmas, New Year, and Thanksgiving. Below I've charted out U.S. cash demand over the decades. The Christmas spikes are quite clear, although they have been getting smaller.

Source: Moneyess blog

The seasonal spikes in U.S. note demand are likely caused by Americans, not foreigners. Foreign demand for U.S. notes is comprised mainly of $50 and $100 notes. These denominations are too awkward to be useful for making the sorts of transactions one typically makes during holiday time. And international drug dealers aren't likely to spend their stash on Christmas presents.

The foreign demand for U.S. notes thus dulls the amplitude of U.S. seasonal note spikes. The degree to which U.S. seasonal spikes are muted relative to Canadian ones gives a good indication of how much U.S. currency is held overseas. Using this method, Judson finds that around 70% of all U.S. currency is held overseas.

Note broker information

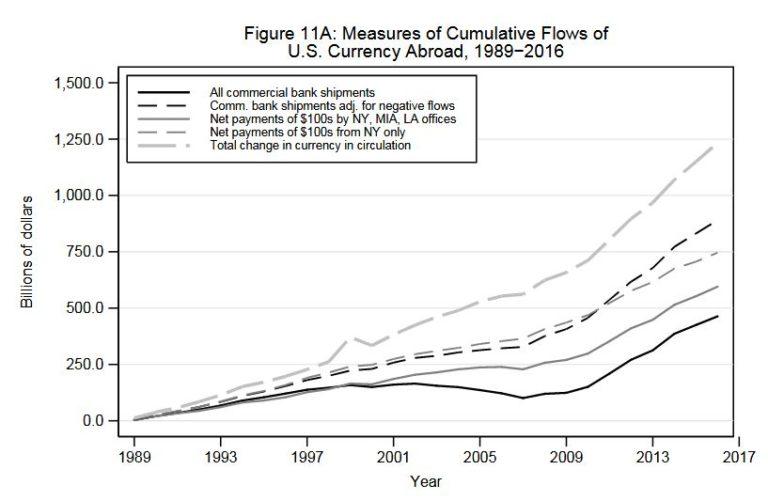

Banks acting as note brokers go to Federal Reserve cash offices located around the U.S. in order to fill both domestic and foreign orders for banknotes. When these banknotes are no longer demanded, banks import them back into the U.S. and redeposit them at the local Fed cash office.

Most of these banks report the destination and source of banknotes. These reports allows Judson to reconstruct the amount of banknotes residing overseas. In the chart below, the solid black line indicates that between 1989 and 2016, a net amount of almost $500 billion in cash was moved by commercial banks to foreign destinations. Meanwhile, the total amount of cash in existence, the bold dashed grey line, has increased by almost $1.25 trillion since 1989. This would indicate that the quantity of banknotes held externally amounts to around 40% of the total (500/1250), which is quite a bit lower than the earlier estimates based on Canadian note preferences.

Source: Judson (2017)

Note broker information doesn't provide a complete picture of the quantity of notes residing overseas. Retail movements of banknote, say notes brought out of the U.S. in people's wallets or suitcases, are not captured. Nor does it capture flows via the mail.

Judson attempts to correct for this in her 2017 paper. She identifies situations in which large commercial bank inflows into the U.S. from certain countries may be due to individuals bringing U.S. cash into that country. Mexico is a good example of this. Immigrants and tourists carry large amounts of cash over the border into Mexico, but these amounts tend to return via official bank channels.

In the chart above, the black dashed line commercial bank shipments adjusted for negative flows attempts to capture the effect of missing retail flows. This series implies that 72% of all banknotes reside outside the U.S.

Shipments from the New York, Miami, and LA cash offices

The Federal Reserve has 28 cash offices distributed around the U.S. that dispense new cash and take in deposits of unwanted cash. Of these 28 offices, New York, Miami, and LA are known to accept substantial deposits of incoming foreign banknotes from banks and withdrawals of banknotes for export internationally.

This provides another way to estimate the amount of banknotes overseas. Assuming that all banknotes flowing into and leaving New York, Miami, and LA are to or from foreign destinations, those flows can be summed up to arrive at a stock of banknotes held outside of the U.S. In Judson's chart above, this is the solid grey line Net payments of $100s by NY, MIA, LA offices. It indicates that around 48% of U.S. cash circulates outside of the border.

For those who want to track the NY/MIA/LA statistic, the Federal Reserve updates it each quarter and includes it in section L.204 of the Flow of Funds Accounts. It also appears on FRED, the Fed's free online data retrieval tool.

The U.S. taxpayer benefits

All this is to say that there are a lot of U.S. banknotes overseas. But as Judson's work illustrates, there is a wide range of estimates to exactly how much.

To what degree do Americans benefit from foreign acceptance of U.S. cash? Let's assume that 60% of all U.S. banknotes have been exported. So out of the $1.738 trillion the Federal Reserve has issued as of this June, $1.043 trillion is held internationally.

The nice thing about banknotes is that the issuer, the central bank, doesn't have to pay any interest on them. This means central banks gets to withhold all of the interest that they receive on the low-risk assets that back the notes that they have put into circulation. It is safe to assume that the Federal Reserve earns the risk free rate of 2.2% on its assets (the 3-month t-bill rate). So that means that the Fed is currently earning $22.9 billion each year from foreign currency owners (2.2% x $1.043 trillion).

The Fed remits this $22.9 billion in earnings to the government. It retains a small amount to pay for expenses. On a per capita basis, the equates to a yearly dividend of $70 for each American! For taxpayers, the U.S.'s greatest export is truly a profitable one.

Commenti

Posta un commento