As if China did not have its hands full with a trade war, a plunging yuan and growing civil unrest in Hong Kong, which is fast becoming the potential epicenter for the next global crisis (and which Steve "The Big Short" Eisman thinks is the next black swan), it now also has deflation to worry about at a time when its ability to boost liquidity in the system is severely limited... or maybe it's soaring inflation China should be concerned about.

On Friday, China's National Bureau of Statistics reported that the Producer Price Index (PPI), i.e. factory prices, fell 0.3% in July from a year ago, missing the modest 0.1% decline expected by analysts. This was the first annual decline in China's PPI in three years - since August 2016 - and just like back then, was largely the result of tumbling commodity prices which in turn depressed both manufacturing and raw material goods prices. And with oil sliding, and iron ore plunging, not to mention the whole trade war thing, it does not seems like a rebound is imminent at all.

Worse, since PPI is closely linked to corporate profitability, the decline suggests that China is badly lagging in the credit impulse arena despite having started off 2019 with a bang and some of the biggest increases in Total Social Financing on record.

So what's the big deal: China has always been able to boost inflation, all it had to do was turn on the credit spigot and inject a few trillion in new bank and shadow loans into the economy.

Maybe that was the case in the past, but this time it will have a big headache, because even as PPI declined for the first time in three years, consumer prices jumped 2.8%, and coming in hotter than the 2.7% expected, were tied for the highest annual headline inflation since February 2018; before that one would have to go all the way to 2013 to find a hotter CPI print.

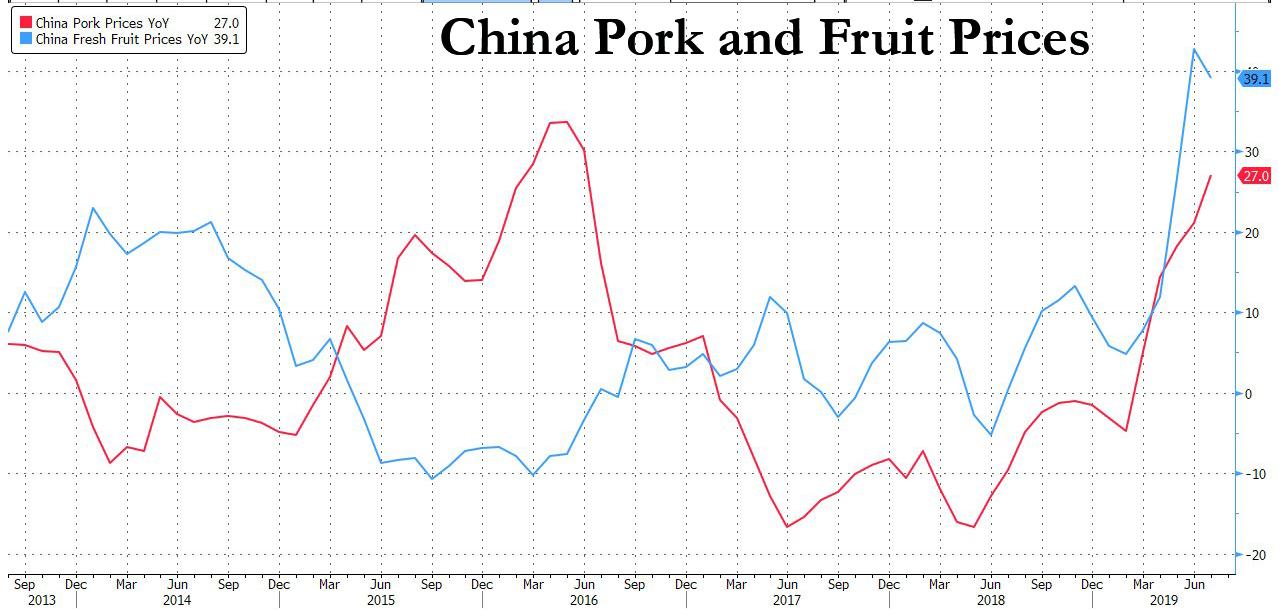

A continuation of recent trends, the bulk of the inflation was the result of sharply higher food prices, which surged 9.1% Y/Y as China continues to battle the rapid spread of "pig ebola" which some expect will eradicate half of China's entire pig population, leading to even higher prices.

Sure enough, pork prices soared 27% in July from a year ago, the highest in three years, but that wasn't even the worst of it: the prices of fresh fruit soared by 39%, the highest since 2006!

This combination of lower factory gate prices and soaring consumer prices is, needless to say, the worst possible outcome for Beijing, whose firepower to stimulate the economy using conventional means is severely limited; that this comes at a time when China is caught in an ever escalating trade war with the US certainly doesn't help.

"Surging pork prices continued to push up consumer price inflation," said Capital Economics economist Julian Evans-Pritchard, but "weakening demand dragged producer price inflation into negative territory last month."

This, as Bloomberg's Kyoungwha Kim writes, is "an ominous sign for equities because it underscores the difficulties the PBOC faces if it wants to boost policy stimulus."

Between soaring food prices, which limit the PBOC's ability to "shotgun" inflation higher by injecting a cool trillion in new debt here and there, and the yuan's plunge past 7 per dollar, this has effectively tied the PBOC's hands, and its ability to ease aggressively as the economy continues to slow.

"The recent episode where the central bank reported to the police false information circulating about rate cuts underscores the policy dilemma that is brewing", adds Kim.

However, it was the first drop in the PPI since 2016 that spooked traders, and first sent Chinese bond yields lower, and shortly thereafter, the Shanghai Composite, amid renewed fears that China is facing a hard landing, and who knows - maybe well before the 2020 US presidential election: "That underscores that rates traders are much more worried about the economy's downturn than rising CPI."

Indeed, as Evans-Pritchard ever so diplomatically put it, with accelerating consumer prices and the return of factory-gate deflation, "the upshot is that China faces the worse of both worlds."

Who knows: a few more downward nudges to the Chinese economy, and Trump may win the trade war against Beijing well before the 2020 presidential election.

Commenti

Posta un commento