With China scrambling to reboot its economy after the record collapse in February as the coronavirus epidemic paralyzed the country, two weeks ago Beijing reported that a remarkable V-shaped recovery had taken place as the country's official manufacturing and service PMIs soared in March...

...a jump which prompted a fair bit of cynical smiles about the validity of China's "data", especially since real-time indicators of China's economy (as tracked by Goldman) demonstrates that Chinese output and activity is still far below normal.

So how did China manage such a spectacular recovery in March?

The answer: the same way China recovers every other time too - by flooding the economy with credit.

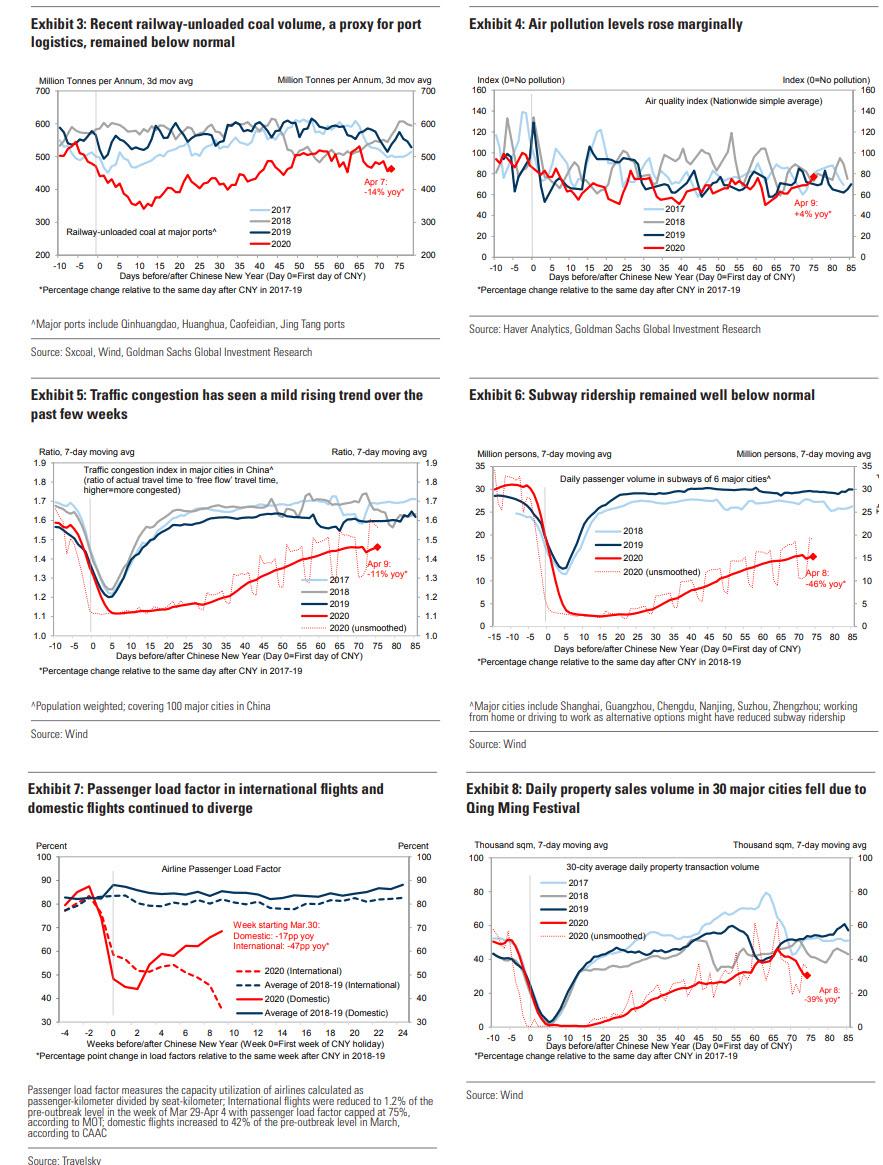

According to data released overnight by the PBOC, in March China's total social financing (TSF) rose to a record high 5.15 trillion yuan ($732 billion), compared to just with 855 billion yuan in February, and nearly double the 3.14 trillion consensus. As a reminder, in addition to new loans, TSF includes off-balance-sheet forms of financing that exist outside the conventional bank lending system, such as IPOs, loans from trust companies and other shadow banking conduits, and bond sales.

The surge in new credit was driven mainly on higher-than-expected loan growth and corporate bond issuance. This, according to Goldman, "demonstrates that the government has been quietly loosening policy, and will likely loosen it more in other areas too, especially given weaker external demand, fairly tight virus control measures and the leadership's desire to maintain growth stability."

China's outstanding TSF was 262.24 trillion yuan or a record $37.3 trillion at the end of March, up 11.5% from a year earlier, and growing at double the rate of the overall economy. This is also roughly three times China's GDP, which suggests that in order to kick start the economy, China is taking on a massive gamble, because if those loans turn bad and the local population is unable to pay them down, then not even the PBOC will be able to prevent the epic financial crisis that will ensue following the coming wave of mass consumer defaults.

Some more details on the latest credit numbers:

- New CNY loans: RMB 2,850Bn in March vs. consensus: RMB 1,800bn. Outstanding CNY loan growth in March of 12.7% yoy was well above the February annual increase of 12.1% yoy.

- Total social financing (flow, reported): RMB 5,150bn in March, vs consensus: RMB 3140bn. TSF stock growth was 11.6% yoy in March, higher than 10.8% in February. And this is how China hit the afterburners on credit growth: the implied month-on-month growth of TSF stock accelerated to 17.8% (seasonally adjusted annual rate) from 12.4% in February.

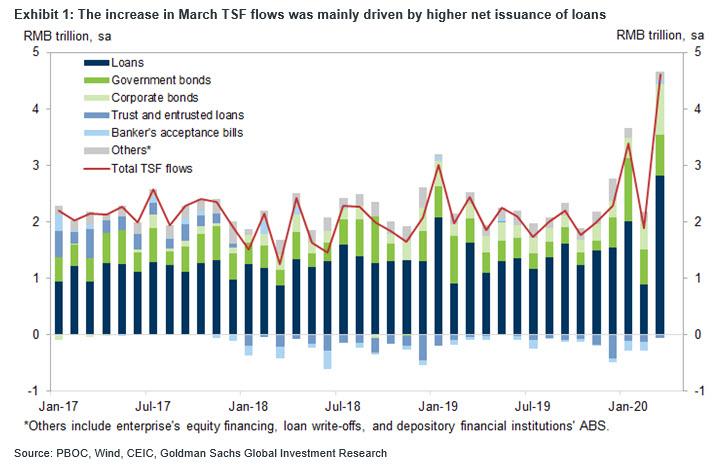

- M2: 10.1% yoy in March vs Bloomberg consensus: 8.8% yoy, and up sharply from February's 8.4% yoy. M2 growth accelerated meaningfully to 10.1% yoy in March from 8.8% in February, the fastest since March 2017 as China flooded the economy with new money.

Also worth noting: for only the 4th time in the past two years, the shadow banking components of the Total Social Financing number posted a sharp rebound, reversing the long-running trend of deleveraging China's highly risky shadow banks which nearly crushed the financial sector in 2017 forcing Beijing to launch an aggressive deleveraging campaign. This means that in order to reboot the economy, China is now willing to go back to the riskiest - and most unsustainable - sources of funding.

As shown in the chart below, after stagnating for years, both TSF and M2 posted a dramatic rebound in March, one which the PBOC will likely seek to extend, even though the broader economy is growing in the low single digits at this moment.

The March data demonstrated two things: that the V-shaped recovery in China's economy in March was not the result of some miraculous return of normalcy in record short time, but merely a flood of cheap credit unleashed by the government; it also showed that the government has been quietly loosening policy more than what it may appear by looking at the magnitude of rate and RRR cuts.

According to Goldman, this preference for quantitative tools could be because of the preference for flexibility amid the unusually high level of uncertainty from the pandemic as "this uncertainty requires real time fine-tuning, which is much easier with quantitative controls on TSF. In contrast, it would be very confusing to cut RRR in one month and hike it the next." Furthermore, quantitative tools are relatively low profile, which fits the preference of the government in terms of the image it wishes to project, especially given the debatable but widespread criticism on the 4 trillion RMB stimulus of 2008.

The relatively high level of CPI inflation recently was also cited by the PBOC as a reason why they hadn't cut the benchmark deposit rate. But March CPI fell by more than expected and high frequency data consistently indicate April CPI will likely be meaningfully lower still. At the same time PPI fell significantly in March and is most likely to continue to fall in April.

So if April CPI inflation comes in at below 4% and PPI under -2%, then it will be much more difficult to argue against a benchmark rate cut based on inflation concerns. PBOC Monetary Policy Department Director General Sun Guofeng said in the press conference that the benchmark deposit rate will not be abolished. Some banks have already started to lower actual rates even if that hurts them in the process - so low is loan demand right now in China! The PBOC can effectively guide these rates down further without cutting the benchmark, which is a possibility. He also indicated the transmission of monetary policy is more efficient in China than in the US, as the increase in loan extension per unit of liquidity injected is higher, so liquidity glut is not a problem in China.

According to Goldman, Beijing needs to loosen more in other areas too, especially given external demand is weakening rapidly, the virus control measures incrementally got tighter in some areas and the clear desire from the top leadership is to maintain growth stability. The bank also expects exports to show a meaningful rebound in March but this is likely a brief sweet spot between the January-February situation, when there was enough external demand but limited domestic supply, and the April-May situation which would be the opposite. As shown in the chart above, this is likely why some high frequency data such as the coal consumption for electricity has shown limited further recovery since late March.

Meanwhile, President Xi indicated the government is ready to keep the virus control measures for an extended period of time as needed in the most recent Politburo standing committee meeting. Although the previous Politburo meeting stated a special national bond will be issued, there is still a lack of clarity in terms of the amount of issuance. Until then, it will be virtually impossible to have confidence about the expected sequential recovery assumed in various bank forecasts.

One final point: it is doubtful if the PBOC will keep TSF growth at this level on a sustainable basis, since it is literally off the chart. While ample credit growth will be needed, recently the central bank appears to have a tendency to control liquidity supply (i.e., credit growth tumbles) in the month that follows a month with a particularly strong number. This happened in February (very weak) after a very strong January. If this happens again it would pose severe downside risks to Chinese rebound forecasts.

Commenti

Posta un commento